China has expanded an unprecedented 10-year ban on fishing in the famed Yangtze River to all its s natural waterways and tributaries to help restore the damaged river.

The ban, to take effect on March 1, covers more areas after the 10-year moratorium on fishing was originally instituted in January last year, covering 332 conservation areas in the 6300km river.

“Though China has been imposing a yearly three-month fishing ban since 2003 to protect the river, the results are not promising, says Cao Wenxuan, an academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

“The new decade-long fishing ban is crucial and unprecedented, which can restore the river’s damaged ecological system, as well as promote sustainable use of natural resources.”

For thousands of years, Baiji (the white-fin dolphin) was regarded as the goddess of protection by local fishermen and boatmen. The beautiful animal appeared in countless historical records and literature, revered by the Chinese for its elegance and beauty. However, over the past few decades, toxic waters, unsustainable fishing and collisions with shipping traffic all sealed the Baiji’s fate – it was declared functionally extinct in 2007.

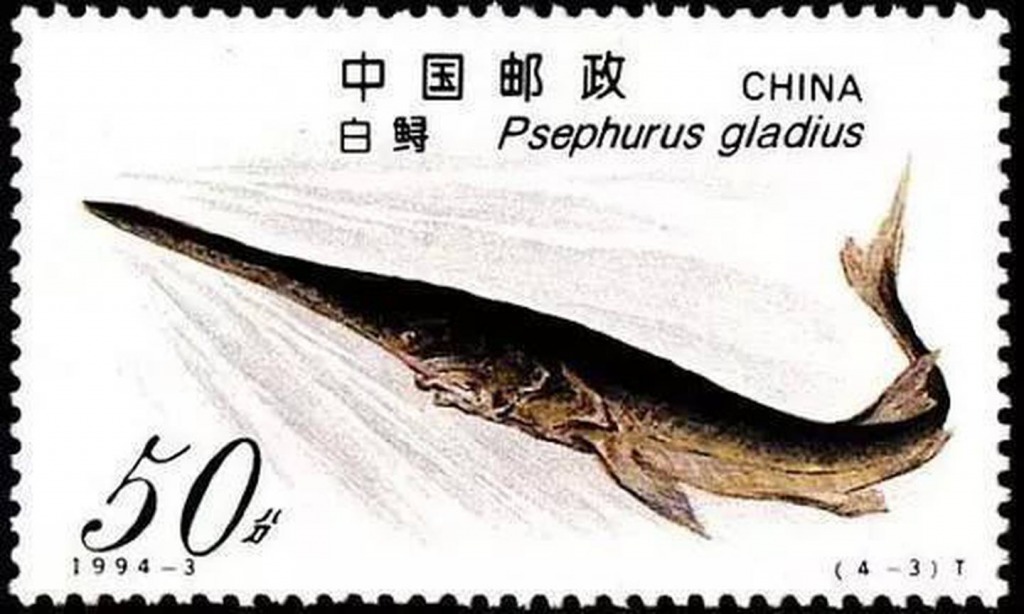

The Baiji is not the only animal eradicated from the river by human activities. The Chinese paddlefish, one of the world’s largest freshwater fish species and a native of the Yangtze River system, has been declared extinct. Less well-known species, such as the finless porpoise, now face extinction.

The Yangtze River is home to 424 types of fish, of which 183 are endemic; the freshwater fish in the river comprise 33 per cent of the national total. Experts say there is not much time left to protect the river’s ecological system before more animals follow the Baiji’s fate, causing great loss to China’s biodiversity.

“The extinction of the Baiji stung the collective conscience of the Chinese people. The remaining fish’s fate foreshadows the health of the whole river ecosystem, so the crisis is also our own,” says Jiang Meng, secretary-general of the Nanjing Yangtze Finless Porpoise Conservation Association.

The alarming situation has made the environmental protection of the Yangtze River, rather than large-scale development, the dominant focus of China’s river development plans.

At a symposium on comprehensively advancing the development of the Yangtze River Economic Belt held in November, Chinese President Xi Jinping noted that the restoration of the ecological environment of the Yangtze River should be a major priority. He added that protection and restoration of the ecological environment should be reasonably rewarded, while those responsible for the ecological environment destruction should pay a due price.

Since the new decade-long ban took effect in January, nearly 100,000 fishermen on 80,000 boats have given up their nets, while the full-scale ban is likely to affect more than 113,000 fishing boats and nearly 280,000 fishermen in 10 provincial regions along the river.

Local authorities along the river have also been launching new environmental-friendly policies to cope with the 10-year fishing ban. Jiangsu Province, in the lower reaches of the Yangtze, closed more than 6000 chemical firms near the river in the last three years. Chongqing aims to remove all companies with dilapidated equipment from the river by 2020.

“Official clampdowns on overfishing and polluting activities have gradually restored the water quality of the Yangtze. The ban may not be very timely, but it can surely save the river,” Jiang says.

Though the world’s third-longest river, the annual catch from the Yangtze has fallen to less than 100,000 tonnes from more than 420,000 tonnes in 1950s.

“Fishermen were caught in a vicious circle — the more they fish, the poorer they become because of the worsening environment,” says Cao.

The new fishing ban has provided fishermen with new opportunities. Local authorities have opened training courses on welding, computer operation and aquaculture for the ex-fishermen, helping them find new jobs in factories or start their own businesses. For those who don’t want to stay ashore, a new job – river patroller – was created for their needs.

Zheng Laigen, a 44-year-old fisherman from Tongling, eastern China’s Anhui Province, moved ashore after working on a boat his entire life. Taking advantage of his expertise in aquatic products garnered over the years, he is now the owner of a fishing farm and manages about 13ha of ponds, raising crabs, shrimp and fish.

His new business was prosperous last year, with an annual income of about 300,000 yuan (about NZ$64,000). In the peak season during the summer, he had to hire four people to help with his work.

Unlike Zheng, Zhu Changhong, also from Tongling, continues to live by the river with his wife in a different way.With the help of the local government, the couple joined a patrol team to clean floating trash and report sightings of finless porpoises, a job that earns them 5000 yuan a month (about $1100). Instead of fishing on the river, now Zhu and his wife patrol 10 to 15 km of water per day on average, collecting up to 200kg of trash on a busy day.

Zhu told Xinhua the river is now recovering little by little, with more fish and birds seen along the river: “It reminds me of my childhood when I see finless porpoises again during the patrol. It’s an honour to protect these angels of the Yangtze River.”